Speech therapy… What is it, what can it do? Most people know that speech therapy helps children to pronounce words correctly. How far-reaching this investment is, however, is often not. If children learn to use language well and confidently at an early age, they have a better chance of a good education and therefore a higher income in later life. Many studies show that for every euro invested in speech therapy, six to seven euros are returned to the community. Other core areas of speech therapy focus on reducing the consequences of the disease rather than curing it completely: One of the most common disabilities after a stroke, for example, is a partial or total loss of speech, known as aphasia. This affects an estimated 20,000 people in Austria. Those affected can still think and feel, they just can’t remember the words. Just like when you have only rudimentary language skills abroad. This loss of language has dramatic consequences: Those affected by aphasia fall out of the primary labor market, social deprivation and even loneliness are imminent, and care may be necessary to master everyday tasks.

Robert Darkow is a UAS professor and heads the Institute and the speech therapy course. He specializes primarily in speech and swallowing disorders in old age. In this Science Story, he takes a look at the field of speech therapy, the use case of stroke, the current care situation and future challenges.

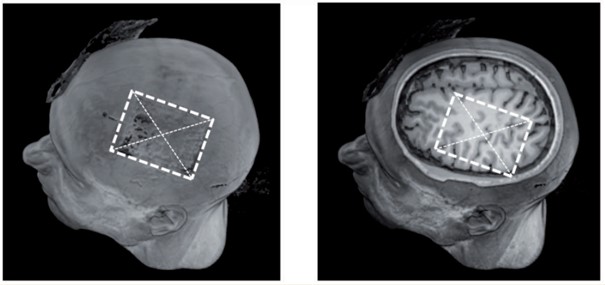

Location of the electrodes, Meinzer&Darkow et al. 2016

Therapy under power

Speech therapy can also help here. Speech therapy significantly improves speech, but the improvements are gradual and hard-won. For this reason, procedures that can support the brain during rehabilitation are being evaluated, including so-called direct current stimulation in the study program. This involves applying a weak current via electrodes attached to the outside of the head. Surface-positive currents can facilitate the work of the nerve cells located under the electrodes. This can improve speech immediately during the therapy session, but with repeated application, the effects can still be measured months later. These linguistic improvements can be seen both at the trained level, for example in word finding, but also in everyday life: relatives report that the speech of their aphasic relatives has improved. Functional imaging showed that not only were the nerve cells under the electrode able to work more easily, but all speech-relevant areas were in better contact with each other. As direct current stimulation also has hardly any side effects and is easy to use, it could be easily integrated into everyday therapeutic and speech therapy. Studies on this are currently underway at the study program.

Speech therapy needs to be more accessible

As promising as this support for speech therapy is, it does not mitigate some disadvantages. Firstly, as a supplement to speech therapy, it is dependent on speech therapy. And that is a problem: speech therapy is not readily available to people with aphasia, even though it is urgently needed: There aren’t enough speech therapists available, and too few speech therapists specialize in aphasia. The systemic processes, such as constantly having to obtain new prescriptions for speech therapy from doctors, represent major obstacles for people with speech and often motor impairments. In our studies, we try to identify these challenges and develop solutions.

Secondly, our society functions through language. Language is THE tool for a successful life, the basis of self-image, the key to the world. Language is a prerequisite for participation in social life. Not being able to speak is not part of our society. This means that the loss of language directly entails the risk of no longer being able to be part of society. Unfortunately, we see this process very clearly with aphasia: in contrast to many other clinical pictures, society does not know about aphasia, cannot deal with it and withdraws. Yet dealing with aphasia sufferers on a day-to-day basis is not complicated; it requires patience, genuine interpersonal interest and empathy. And it needs a lobby: aphasics naturally cannot stand up for their wishes, needs and requirements. This requires our support.